For Teachers

Model for Success Condition and Guidelines for teachers on the use of digital games in geography classes.

Guidelines for teachers on the use of digital games in geography classes

Joelle-Denise Lux & Alexandra Budke

Digital games as interactive media offer unique potentials for education, such as the opportunity for explorative learning (Van Eck 2006), practicing problem-solving (Gaber 2007), or enhancing learning motivation (Arnold, Söbke & Reichelt 2019), amongst others. Many entertainment games in fact do represent content relevant for geography education, for instance content on current societal issues such as climate change or resource conflicts. Aside from making use of their positive potentials, digital games should be reflected in formal learning contexts (Medienberatung NRW 2020:21), as adolescents are in regular contact with the medium in their free time (MPFS 2018:57) and are surely influenced by the content presented. As such, it is the responsibility of school teachers to build up a competence to deal with this kind of medium – and in turn the games give them the opportunity to create more compelling and possibly more effective lessons. The following guidelines shall aid teachers, in particular geography teachers, to do so.

The guidelines are based on our research within the project DiSpielGeo. To date, games, particularly entertainment games, have not been well-researched in the context of education on complex societal topics, which are major topics of geography education. Within the project DiSpielGeo we, researchers from the Institute for Geography Education of the University of Cologne and from the Cologne Game Lab of TH Köln, conducted a range of studies on the potentials and limits of digital entertainment games for geography education (Czauderna & Budke 2020, 2021, Lux & Budke 2020a, 2020b, Lux, Budke & Guardiola, in preparation). These studies focused mainly on strategy and simulation games, such as SimCity, Cities: Skylines, Tropico 6, and similar, which cover at least one among the societal topics of climate change, resource use, urban development and migration. Our studies consisted of analyses of their complexity, content, decision-making design and significance for political education, as well as of interviews with game designers and players. With these studies, we do not only want to contribute to the body of academic literature that explores games in an educational context and to refine the research particularly concerning geography education, but we also want to derive practical guidelines for all involved in the design and classroom use of geography-relevant games. The following guidelines are for teachers who are open to utilize the complex medium of games to create meaningful, but also exciting geography lessons, and thus shall aid educators to do so. These guidelines are not meant to cover all aspects relevant in this context, but they include all insights we could gain from our ground research on entertainment games that cover geography-relevant, complex topics. However, we are open to well-grounded suggestions for changes and additions – feel free to contact us via e-mail to info@dispielgeo.de.

1. Selection of Games

When having decided to integrate digital games into your geography lessons, the question arises which game to use. Various authors argue that serious games are not the only valid choice for edu-cational purposes. As our research has shown, entertainment games that center on social or socio-ecological challenges cover many aspects of geography curricula (Lux & Budke 2020b). Deviations from a realistic representation can as well be useful, as an incentive for a reflection in class and for fostering critical media literacy (Lux & Budke, 2020b; Lux, Budke & Guardiola, in preparation; Van Eck, 2006). An additional argument in favor of using commercial games is that educational games are often less motivating, less complex and offer less freedom of action (e.g. Shen et al. 2009). As such, we recommend to be open for such commercial games. In the following, we have collected some criteria that shall aid making the choice for the right game for your purpose.

There are also several platforms on the internet that aid teachers and parents to find games that are appropriate for a certain age and educational goal, and partly offer didactical material.

Websites in German:

- “Spieleratgeber NRW“ (https://www.spieleratgeber-nrw.de/)

- “Zentrum für didaktische Computerspielforschung” (http://zfdc.janboelmann.de/material/)

- Unterhaltungsspiele Selbstkontrolle (https://usk.de/)

1.1 Regarding general determining factors, consider technical preconditions, topic, age appropriateness and accessibility!

The first determining factors for the choice of games are the technical preconditions in class and among the students, the geographical topic, the age appropriateness and the accessibility of the game for players with varying expertise as well as for the given time frame.

First and foremost, the general preconditions narrow the choice of games. The first decision to be made is the platform of the game, meaning computer or mobile devices. Generally, we recommend using computer games – when it comes to teaching complex geographical topics – as they are commonly more complex than mobile ones (see Lux & Budke, 2020a:28), due to the latter being designed for small screens and casual gaming sessions “on the go”. PC games have varying technical requirements, there are usually options for any kind of school computers, and there are options for cloud gaming that allow technically demanding games to be run on older hardware (several providers, easy to find via search engine). If the technical preconditions at school (or the budget, for that matter) do not allow for individual gaming during the lesson, there are other options to include the game in class (see also “3: Incorporating the game into class”). In case computer games are not an option, mobile games can be a valid choice as well, if they do present enough geographical content (see section 1.2) and if the simplifications are well-reflected upon (see “4: Debriefing”). They have the advantage of being easy to implement because almost all students have smartphones and therefore the necessary hardware is already available. They also allow for more flexible playing times.

Naturally, age appropriateness is a factor as well. Commonly, simulation and strategy games only involve violence when they center on military strategy. City builders, economic simulations and general political simulations are, from our experience, usually safe for young players. However, appropriateness does not only involve the official age recommendation (for example by “Unterhaltungssoftware Selbstkontrolle” (USK) on https://usk.de/ or by “Pan-European Game Information” (PEGI) on https://pegi.info) due to levels of violence, harsh language and the like, but also the appropriateness of the content with regard to the curriculum. When it comes to content appropriateness, the game should at least cover some of the relevant aspects of a curricular topic. This does not mean that the game needs to be highly realistic in this aspect, as it is also valuable for media literacy and gaining subject knowledge to compare a game’s simplifications with reality (Van Eck 2006:23) (see “4: Debriefing”). Also, some games assume a certain level of prior subject knowledge (for example, Democracy requires you to know what the GDP is), which in turn influences their suitability for different grade levels.

Aside from these general determining factors, the game also needs to be accessible for both learners and the teacher. For one, games should be well-understood by educators before bringing them into classroom settings, or else important aspects for reflection may be missed out. Apart from playing the games, sources of information on the games are gameplay videos (so-called “Let’s-Plays”) on platforms like YouTube, or game Wikis (which can easily be found via search engine). As such, complex games demand a certain level of previous experience from teachers, or dedication to engage with them in the preparation phase. Mobile games are commonly easier to understand, which may influence the platform choice as much as the technical preconditions.

Relevant for the accessibility (and the feasibility in class) is also how much time it takes to encounter the geographical topics in the game – are they relevant from the start, or do players need hours before they need to make geography-relevant decisions? At best, the curricular topics are the main themes of the game and directly linked with success conditions. For example, main topic of Fate of the World is climate change, so pupils deal with the geographical issue right away, while in Civilization VI – Gathering Storm it takes several hours until climate change becomes relevant, which makes the game more suitable for project weeks, voluntary work groups after class or informal contexts. To find out how much relevance a geographical topic has for the game considered, you may use the recommended internet platforms, as well as websites of game journals (such as www.gamestar.de), and trailers on YouTube or on game distribution platforms such as Steam. There, you may also research whether a game is multiplayer (cooperative or competitive) or for single players, which influences the extent of collaboration in class during play and may also be a factor in making the choice.

1.2 Regarding content, consider the depiction of socio-ecological challenges and system complexity!

Societal challenges are complex – games to be chosen for a use in class should represent the con-troversy, multi-perspectivity and systemic complexity of these topics to a certain degree.

Aside from general factors that have to be considered, the geographical content is the most important aspect to consider when choosing a game for use in class. When utilizing games to educate about complex societal challenges, the game systems should be geographically complex to a certain degree (depending on age group and school form). This means that games should at least partially represent the complexity of geographic systems, with their various actors, scale levels, and system relationships.

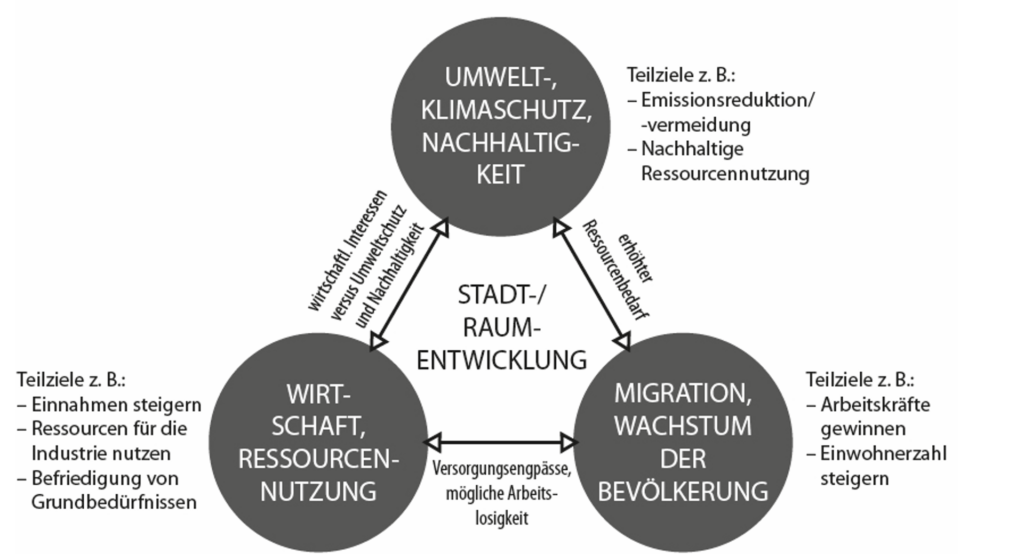

For one, we recommend to choose a game that represents at least two geography-relevant societal topics, such as climate change and resource use in ECO or Civilization VI – Gathering Storm, city development and resource use in Cities: Skylines or city development, migration and resource use in Tropico 6 (for an overview of topics in our game selection, see Lux & Budke, 2020b:25). This enables the depiction of interconnections between different social or socio-economical phenomena and resulting conflicting goals, which can then be discussed in class to build up system competence. The following graph shows in an exemplary way which conflicting goals in the context of societal issues we found in one of our game analyses (Lux & Budke, 2020b:33) – these are for example the goals of emission reduction for climate protection and ecological sustainability that are in conflict with goals of both economic and population growth (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Selection of conflicting goals within the analyzed games (Lux & Budke, 2020b:33). übersetzen

Such conflicting goals in decision-making are common in real-life complex issues, and games can put players into the position to make those decisions which are usually beyond their control (Lux, Budke & Guardiola, in preparation), which enables them to practice dynamic decision-making in such complex geographical contexts (Czauderna & Budke, 2020). Therefore, games that connect two or more geographical topics are particularly valuable for a use in class.

Then, it is important that legitimate positions to the chosen topic, in the sense of the Beutelsbach consensus[1], should be represented (as recommended by Czauderna & Budke, 2020), as well as multiple perspectives on this issue. In games, this can be done for example through the inclusion of different actors who have different perspectives on the problem and through whom the immanent conflicts become understandable, for example voter groups or interest groups, such as the political groups in Democracy or Tropico. If the game in question includes such actors, this is a good first reference point for multiperspectivity. Also, actors increase the systemic complexity – in real life complex issues, various actors always play a role (Müller, 2016:37 ff.). The games should as well allow players to explore multiple paths to success, to try different approaches (Czauderna & Budke, 2020). As such, simulation and strategy games are a recommended genre according to our studies, because the oftentimes overpowered roles players incorporate in such games give them the opportunity to experiment with different solutions. Adventures, action and puzzle games can be educative as well, but do not usually offer that much unscripted freedom of choice.

[1] The Beutelsbach Consensus consists of three principles which intend to establish a minimum standard in civic education. The three principles say that it is prohibited to steer pupils in a specific political direction, that controversial content should be presented as controversial, and that the personal interests of pupils should have a high weight in education.

2. Preparation

During the preparation phase, teachers should intensively engage with the game, make all the necessary technical preparations, and create the material for debriefing.

As we do recommend the use of games which represent complex geographic systems (see 1.2, and Lux & Budke 2020a), it is required to explore the game intensively before bringing it into class. Else, potential might be lost if important aspects are overlooked in the discussion, particularly aspects which students do not bring up themselves (Peters & Vissers 2004:81), or if you cannot answer students’ questions about the game.

If this basis is established, it is time to turn to the technical preparations. Considerations that teachers should make during that phase:

- • How many PCs/ other devices are needed? For mobile games: Do all students have a suitable smartphone or are school devices needed? For PC games: Can the school equipment be supplemented by (the students’) private gaming laptops?

- • Is other technical equipment needed? (Boxes, beamer, ...)

- • How does the installation of the game work? The games should be installed before the lesson starts!

- • How to cover eventual costs for games and equipment?

Then, it is time to create the lesson plan. It is crucial to set learning goals and establish the link to the curriculum. The lesson should start with a preparation for the problem or question that should be solved or explored in the game. Thus, it shall introduce the problem, activate the students’ previous knowledge and evoke interest in the topic. For example, a lesson on city development that uses a city builder game (such as Cities: Skylines or SimCity BuildIt), could start with impressions from the city the students live in, to connect to the personal life of the pupils. Before starting the playing session (or streaming session, depending on how you chose to include the game; see section 3), it is also important to schedule time for explaining the sense of playing the game, and a precise task should be connected with the playing session. Also, enough time should be scheduled for the reflection, since it is as important as the gaming part itself (see section 4).

An important step of the preparation phase is considered with the procurement or creation of material. Depending on the learning goals and the reflection that should take place, respective material for debriefing is required – for example if the lesson shall concern the complexity of city development (with the help of SimCity, Cities: Skylines or similar), you may need informative texts or interviews with real actors in urban development, amongst other things.

Lastly, you may want to consider to inform the parents beforehand, particularly if students need to bring their own devices for the lesson, or if they have to play as homework. Informing them about the purpose of the lesson may be necessary for the parents to allow their children to use the equipment, since gaming is oftentimes associated with addictive behavior. An information sheet should explain the sense of playing the game and it should clarify how long the students need to play it at home. If a free-to-play game is used, information should also be provided about possible in-game stores, so that students do not inadvertently make purchases with real money.

Incorporating the game into class

When it comes to integrating the game into the lesson, teachers have the choice to either let pupils play the game themselves, to play it collaboratively via beamer, or to show and discuss gameplay videos. All of these methods have advantages and disadvantages.

To make full use of the games’ potential, students should get the opportunity to play the games themselves – either in class, in extracurricular courses and projects, or as homework. Actually playing the games enables the students to experiment and explore different solution strategies to geographical problems on their own, as well as to share their own experiences in the debriefing phase. In schools with little technical equipment and budget, free mobile games such as SimCity BuildIt and Pocket City are an option (see “1: Selection of Games”).

If you have selected a PC game and the technical preconditions at school or the budget do not allow for individual gaming in class, it is an option to play the game together on one device via projector. In case no options are given to play any or a certain game in class, the option remains to show gameplay videos (for example on YouTube) and discuss game experiences (part of) the pupils made in their free time. This may mean that a lot of potential is lost, especially if students have not played themselves in their free time, as first-hand experience, in every discipline, is particularly instructive (Montessori 1949); however, it can still be a fruitful lesson, if enough time is scheduled for the reflection.

The gaming session should be connected to a precise task and the overall learning goal of the lesson. If for example the lesson is about learning about the causes of climate change, then the task for the playing session (e.g. with ECO or Democracy 3 and 4) could be to try out different political approaches in the game and note down how they influence climatic change. Or if you plan a lesson on getting to know the functions and functional structure of a city, you can use a city builder (for lower grades mobile games such as SimCity BuildIt or Pocket City are sufficient, for higher grades we recommend the more complex PC city builders), give the task to include as many functions as possible in the own virtual city, and afterwards discuss how the pupils structured their city and why. In case you can only include gameplay videos or play via beamer, there should be a task while watching nonetheless.

We recommend that results from this phase also be documented in writing - in the examples given, for instance, a table on the causes of climate change in the game, or the buildings in the game that belong to the various functions of a city. This can be done in between or after playing sessions. Then, we also recommend to collect the pupils’ impressions on the gameplay session before starting with the reflection. An open discussion on what the students liked and didn’t like about the game is a good option to gather impressions from everyone. Both the written results and the impressions from the game can be a useful basis for the subsequent debriefing phase.

4. Debriefing

Wichtigste Aufgabe der Lehrenden im Kontext des spielbasierten Lernens ist es, eine inhaltsbe-zogene Reflexion zu führen; genauer gesagt, die Inhalte zu hinterfragen, das neu gewonnene Wissen zu sammeln, zu sortieren und zu ergänzen (Lux & Budke, 2020b:34) und über die Mög-lichkeiten und Grenzen des Spiels nachzudenken. Eine solche Nachbesprechung, d.h. sich die Zeit zu nehmen, die Spielsitzung zu diskutieren und zu reflektieren, ist ein wesentlicher Be-standteil jeder pädagogischen Nutzung von Spielen, da sie Lernprozesse auslöst (Crookall, 2010; Kritz, 2010; Schwägele, 2021). Eine Reflexion ermöglicht Lernprozesse, auch wenn das Spiel von der Realität abweicht oder wichtige Inhalte auslässt (Van Eck, 2006:24), und sie stärkt die Medi-enkompetenz der Schüler (Medienberatung NRW, 2020:21). Sowohl die Nachbesprechung in der Gruppe (wie von Peters & Vissers, 2004, empfohlen) als auch das Gespräch über ganz individuel-le Erfahrungen (dessen Bedeutung z.B. von Lederman, 1992, betont wird) sind in diesem Prozess wichtig. Die Reflexion kann am Ende einer Spielsitzung oder zwischendurch stattfinden. Im Fol-genden stellen wir dar, welche Aspekte unseren Studien nach wichtig sind, um sie in eine Re-flexion einzubeziehen.

4.1 Reflect upon the game system in itself!

The first step of reflection on the game is the game system itself, so the representation and inter-connections between topics within the game. Understanding how the geographical system in the game works is the basis for a discussion on parallels and deviations from reality later on.

Before parallels to or deviations from reality can be reflected upon, we highly recommend to take the time to debrief on the presentation of geographical topics within the game. Since the basic concept of geography is the concept of systems (DGfG 2020:10f.), the different parts of systems are a good orientation on which parts of a game to reflect upon in class. For one, the system elements could be taken into focus. The game equivalent to actors and structures/ factors in reality are the virtual actors (players, non-player characters, virtual parties/ interest groups), the controllable parameters (all variables that players can influence indirectly, such as the budget, the level of environmental damage, the number of inhabitants etc.) and the antagonistic factors (everything beyond the players’ control, such as natural disasters or natural preconditions) (see Lux & Budke 2020a:6ff). For example, the actors could be in the focus of reflection, by making the students determine which actors have an influence on a specific geographic issue in the game. For instance, the actors influencing city development in Tropico are the inhabitants as well as local political groups and political partner states. Then, the representation of these actors could be discussed – e.g., is the city population depicted as one mass, or do they have differing needs and opinions, are there even interest groups? The discussion can then be used as a transition to a reflection on parallels and deviations to reality (see 4.2).

In real-world systems, processes are important as well (DGfG 2020:11), so the cause-and-effect-relations and interdependencies within the system. In games, particularly from the strategy and simulation genre, these can be found, too (see Lux & Budke 2020a). Each action in a game has an influence on the virtual world. In the reflection phase you can for example have a look at how the different parameters in the game are interconnected, meaning how changes in one variable (e.g. the number of traffic jams) changes other variables (e.g. the satisfaction of inhabitants and the greenhouse gas emissions), which then again influence the next. Since different scale levels are of high importance to the subject of geography (DGfG 2020:11), it is also fruitful to reflect how actions on one scale level in the game influence other scale levels (for example how local measures can affect global climate change, how local city development influences the surrounding region, or how international migration influences a city). These reflections on the in-game system are a good basis for the later stages of reflection, particularly when it comes to the comparison to reality.

It is as well worthwhile to discuss players’ approaches, solutions, and strategies within the game. According to Charsky (2010:199), the full potential of the problem-based approach used in games can only be utilized in an educational context when the approaches of players are discussed with their teachers and peers in class. In the context of societal challenges, we particularly recommend to reflect upon players’ strategies to deal with the conflicting goals (such as those shown in Fig. 1) they encountered while solving social or socio-ecological issues. Questions to start a discussion could be the following: In which situations did you make the most conflicting decisions? Or, more precise: In which decision-making situations did you need to weigh up between ecological, economical and social aspects? How did you decide and why?

In that phase, it may also be fruitful to have a look at how exactly decision-making works in the game. The decision-making in games is always based on a loop (Czauderna & Budke 2020:5, Salen and Zimmerman 2003:316): A problem/ conflict/ decision-making-situation occurs; the player makes a decision, leading to an action taken, which in turn leads to a reaction by the game that is communicated via feedback, which then leads to new decision-making-situations and gives a basis for the next decision, while time modification and mediation of the choice of actions can assist in the decision-making. This process can be reflected upon in class as well. Questions that can be posed then are for example: Which (geography-related) decision-making-situations did you find most interesting/ difficult and why? What was the outcome of your choice (regarding the geographical issue)? How did the game communicate the outcome to you? Did others in class decide differently and why? In hindsight, what do you think was the most beneficial strategy and why do you think so? Questions like these can as well be used as an easy transition to the next step, the comparison to reality.

4.2 Reflect upon the parallels to and deviations from real-life systems!

The next step of the debriefing should concern the comparison to reality, which is crucial for making the connection to the real-life societal issues and for preventing misinformation.

In an interview study with game designers, we found that intensive research (in the sense of information gathering) on societal issues is carried out when developing a game – however, rarely with the help of scientific sources (Lux, Budke & Guardiola, in preparation). On the one hand, this means that many aspects of the topics shown in common media are interwoven into the game, but on the other, excluding current scientific insights may lead to deviances from the current state of knowledge. Furthermore, we found that external realism, which aims to realistically depict aspects of real life, is oftentimes of lower priority than other forms of realism (ibid.). Of higher priority are internal realism, so game-internal logics that may have no connection to reality, and perceived realism, meaning that commonly believed concepts are depicted (even when they’re wrong) to make the game content seem more realistic. First and foremost, game designers feel an obligation to entertain, and their awareness of their influence on the education of game players varies (Czauderna & Budke, 2021).

Debriefing on parallels and deviances of games from the real world can help to avoid the forming of misconceptions that could stem from these common practices, and it may strengthen the critical view that should be applied when dealing with information from any form of media. As Van Eck (2006:24) suggests, as a first step teachers can let the students discover for themselves at which points their knowledge and the game content clash, to create a “cognitive disequilibrium” (ibid.). Then, we recommend material to be provided that looks at the social issues in question from a scientific perspective, as well as authentic material (e.g., newspaper articles, witness accounts/interviews). In this way, students can compare the game content and their own background knowledge with the state of research and current authentic sources.

During this phase of reflection, it is also helpful to consider the different forms of realism in games and discuss what kind of realism was emphasized more or less in the respective game. When you pick a certain situation in the game, it may for example be discussed whether the situation is internally realistic, so logically coherent, and/ or externally realistic, meaning that it could be like that in reality. Then, the class could determine which aspects of realism were emphasized: Is it graphics and sounds? The actions that can be taken? The story? Or the geographical system with all its actors and factors? An overview of the different types of realism can be found in Lux, Budke and Guardiola (in preparation). Additionally, an idea for debriefing could be the identification of the strategies by which game designers deal with real societal issues. If an aspect is not represented externally realistic, how was it depicted then? Was it completely left out? Or sugarcoated? Replaced with fictional content? For example, slavery in Anno 1800 only appears in the story, but was, according to our designer interviews (Lux, Budke and Guardiola, in preparation), completely left out of gameplay to not depict it as something players can have fun with. A discussion about such strategies may help to raise awareness that game content depends on the choice of its designers. Also, it may aid in identifying the political message of the designers which is interwoven in the game. Thus, a reflection on how designers deal with geographic topics could also counteract an ideological influence, in line with the Beutelsbach Consensus (Czauderna & Budke, 2021:113). It might also be worthwhile to explicitly discuss the tension between commercial intentions and constraints of the developers and publishers on the one hand and political/ educational "side effects" or even political/ educational aspirations on the other (ibid.).With such reflection, media literacy can be further promoted, the way it is required to be fostered in school (e.g. Hobbs & Jensen, 2009; Medienberatung NRW, 2020).

4.3 Let the players reflect upon themselves!

Not only do players learn about the game content while playing, they also discover aspects about themselves. We therefore recommend to take the time for self-reflection, to promote personal growth.

Following the discussion of the game strategies, it is reasonable to also guide self-reflection. While there are different definitions of this term (see e.g. Jahncke et al. 2018:509), in this context, we define self-reflection as the reflection upon the own personality, so preferences, attitudes and character traits.

While gaming, the pupils also learn something about themselves – at the very least about their personality in the game (and those of their fellow players), meaning their playing style, for example whether they rather seek or avoid conflicts in the game and why. If guided well, they may also learn about their (political) attitudes and moral concepts, for example whether they always try to build a sustainable city because this is an important topic to them in real life.

As an incentive for discussion, you may use questions similar to those we posed in our study with players. They can be follow-up questions to the ones referring to the players’ actions in the game (see 4.1) – for example the question “Why did you act in the game the way you did?” can be followed by “Would you act the same way in reality? Why/ why not?”. As our interviews have shown, such questions may trigger reflection on their “gamer personality”. When discussed in more depth, you may also trigger further insights into the own personality, such as the political attitude that may influence the actions taken and the decisions made in the game.

4.4 Reflect upon the medium of games!

A last step to the debriefing could be a meta reflection on the medium of games - a holistic view of the advantages and disadvantages of the medium for learning about social challenges.

On the basis of the play experiences and the previous reflection steps, a meta-reflection on the medium "game" can as well be guided. Meta-reflection in this case means that a distanced view is taken on the medium as a whole, particularly regarding the purpose of its use in geography education. It is easiest to start with a critical view on the specific game used, and then to proceed with general considerations on the medium. Impulses for reflection could be:

- Do the students feel like the game in question did teach them well about the societal topic considered, for example about the interconnections between city development and climate change or about the actors involved in resource use? Why/ why not?

- Do they consider another game more suitable? Or another medium, such as textbooks, movies, etc.? Why?

- Do the students consider games in general a suitable medium for learning about societal topics? Why/ why not?

- Which unique advantages and disadvantages of the medium (compared to other media) do the students see, particularly for the learning about current social challenges and phenomena?

- Which aspects do they think they should they look at critically when they play in their free time in the future?

Discussions like these may help to transfer the lessons learned from the concrete game to the general medium of games, and as such to further complement the students’ media competence.

References

Arnold, U., H. Söbke & Reichelt, M. (2019). SimCity in Infrastructure Management Education. Education Sciences 2019(9), Article 209.

Charsky, D. (2010): Making a connection: Game genres, game characteristics, and teaching structures. In: Van Eck, R. (Hrsg.): Gaming and Cognition. Theories and practice from the learning sciences. Information Science Reference, Hershey. S. 189–212.

Crookall, D. (2010). Serious games, debriefing, and simulation/gaming as a discipline. Simulation & gaming 41 (6), 898–920. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878110390784

Czauderna, A. & Budke, A. (2020). ow Digital Strategy and Management Games Can Facilitate the Practice of Dynamic Decision-Making. Education Sciences 10(4), Article 99. doi: 10.3390/educsci10040099.

Czauderna, A. & Budke, A. (2021). Game Designer als Akteure der politischen Bildung. MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift für Theorie und Praxis der Medienbildung 38, pp. 94–116. doi: 10.21240/mpaed/38/2021.01.25.X.

Gaber, J. (2007): Simulating Planning: SimCity as a Pedagogical Tool. In: Journal of Planning Education and Research 27. S. 113–121.

Hobbs, R., & Jensen, A. (2009). The Past, Present, and Future of Media Literacy Education. Journal of Media Literacy Education 1(1), 1-11.

Jahncke, H., Berding, F., Porath, J. & Magh, K. (2018). Einfluss von Feedback auf die (Selbst-)Reflexion von Lehramtsstudierenden. Die hochschullehre 4 (2018), 505-530.

Kriz, W. C. (2010). A systemic-constructivist approach to the facilitation and debriefing of simulations and games. Simulation & Gaming 41 (5), 663–680. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878108319867

Lederman, L. C. (1992). Debriefing: Toward a systematic assessment of theory and practice. Simulation & Gaming, 23(2), 145-160.

Lux, J.-D. & Budke, A. (2020a). Alles nur ein Spiel? Geographisches Fachwissen zu aktuellen gesellschaftlichen Herausforderungen in digitalen Spielen. GW Unterricht 160, pp. 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1553/gw-unterricht160s22

Lux, J.-D. & Budke, A. (2020b). Playing with Complex Systems? The Potential to Gain Geographical System Competence through Digital Gaming. Education Sciences 10(5), Article 130. doi: 10.3390/educsci10050130.

Lux, J.-D., Budke, A. & Guardiola, E. (in preparation). Games vs. reality? How game designers deal with current topics of geography education.

Medienberatung NRW (2020). Medienkompetenzrahmen NRW, 3. Auflage. Münster/ Düsseldorf: Medienberatung NRW.

Montessori, M. (1949). The absorbent mind. Madras, India: Theosophical Publishing House.

MPFS (Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest) (2018). JIM-Studie 2018 – Jugend, Information, Medien: Basisuntersuchung zum Medienumgang 12- bis 19-Jähriger. Available online: https://www.mpfs.de/fileadmin/files/Studien/JIM/2018/Studie/JIM_2018_Gesamt.pdf

Müller, B. (2016). Komplexe Mensch-Umwelt-Systeme im Geographieunterricht mit Hilfe von Argumentationen erschliessen am Beispiel der Trinkwasserproblematik in Guadalajara (Mexiko). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany, 6 June 2016.

Peters, V. A. M. & Vissers, G. A. N. (2004). A simple classification model for debriefing simulation games. Simulation & Gaming 35(1), 70-84. DOI: 10.1177/1046878103253719

Schwägele, S., Zürn, B., Lukosch, H. K., & Freese, M. (2021). Design of an Impulse-Debriefing-Spiral for Simulation Game Facilitation. Simulation & Gaming 52(3), 364-385. DOI: 10.1177/10468781211006752

Shen, C., Wang, H. & Ritterfeld, U. (2009). Serious Games and Seriously Fun Games. In: Ritterfeld, U., Cody, M. & Vorderer, P. (Eds.): Serious games: Mechanisms and Effects. New York: Routledge, 48–61.

Tekinbaş, K.S. & Zimmerman, E. (2003). Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; ISBN 978-0-262-24045-1.

Van Eck, R. (2006). Digital game-based learning. It’s not just the digital natives who are restless. EDUCAUSE Review 41(2), 55–63.